Justin Marceau, a changemaker in animal law, is one of Vox’s Future Perfect 50 for 2023. This annual list highlights 50 people who are making the world a better place for everyone.

If it weren’t for the animal rights activists who go undercover on America’s factory farms and slaughterhouses, we’d have little idea of the extreme cruelty inflicted on the billions of animals raised for meat, dairy, and eggs each year. That’s why, from the 1990s to the 2010s, meat producers aggressively lobbied for “ag-gag” laws to criminalize such investigations.

But thanks to the work of animal lawyers like Justin Marceau, ag-gag laws have largely been struck down as unconstitutional. Marceau, a law professor at the University of Denver (DU), led successful efforts to overturn Idaho’s and Utah’s ag-gag laws. Now, he’s building out a program at DU devoted to representing animal activists facing prosecution for exposing factory farm abuse.

Last fall, a high-profile trial in southern Utah demonstrated the power of such cases to change how animals are treated under the law. Two activists from the animal rights group Direct Action Everywhere (DxE) were facing burglary and theft charges for entering a pig factory farm owned by meat giant Smithfield Foods, filming the conditions there, and rescuing two sick, suffering piglets. The activists each faced years in prison, even though the piglets were only worth, according to prosecutors, $42 apiece.

Marceau played a small role in defending the activists in that case — and they won, persuading a jury in the middle of Trump country to acquit them while generating a substantial amount of press coverage for their cause.

That surprise verdict “showed for the first time that sometimes it can be legal to take animals from factory farms without the consent of their owners, opening up radically different possibilities for animal law,” wrote Vox’s Marina Bolotnikova about Marceau’s reflections on the Smithfield trial.

That kind of legal victory, in that part of the US, sends a clear message to other prosecutors that might want to go after nonviolent animal rights activists: they could lose.

It was all part of a larger, risky experiment to openly defy laws activists see as unjust in an effort to put factory farming on trial and influence the legal system in animals’ favor. Marceau sees these cases as an essential part of the movement for animal rights. Last year, he launched the Animal Activist Legal Defense Project, a law clinic at DU that represents activists pro bono.

Months after the Smithfield trial activists walked free, a lawyer on Marceau’s team, Chris Carraway, won a similar case in California’s Central Valley, involving activists who rescued two sick chickens from a factory farm. Marceau’s team also worked on a recent prosecution of Direct Action Everywhere activists who removed 70 chickens and ducks from factory farms in Northern California. Earlier this month, the group’s co-founder, Wayne Hsiung, was found guilty in that case and is now being held in jail as he awaits sentencing.

There are reasoned criticisms of such tactics: They could put activists behind bars for years, an outcome Hsiung is now facing, and there’s no guarantee they’ll advance animal law. But the upside of the conviction is that it gives the activists the opportunity to appeal, which Marceau is already working on. If successful, an appeal could create legally binding precedent that advances protections for animals and activists.

Marceau’s team is defending other activists, like Phil Demers, who is facing a lawsuit from Miami Seaquarium for simply posting drone footage of an orca held in extreme confinement there. Next year, Marceau hopes to help introduce legislation to challenge factory farm practices in Colorado.

Marceau’s activist defense work is of a piece with his broader critique of how the animal rights movement uses criminal law. His 2019 book Beyond Cages: Animal Law and Criminal Punishment challenges how animal lawyers have often pushed a “tough on crime” approach that scapegoats powerless ordinary people for animal abuse — a low-income person who neglects their dog, say, or a factory farm worker caught on tape beating an animal when the conditions of their job make it impossible to treat the animals humanely. That approach, Marceau argues, creates a false sense of justice while the meat industry faces little to no consequences for the routine practices that inflict cruelty onto billions of animals.

Change for animals is slow, challenging work, and activists — especially those who employ bold, risky tactics — are likely to face repression from governments and corporations. With the Animal Activist Legal Defense Project, Marceau wants to train the next generation of lawyers to think differently about their roles in that movement — and to fundamentally change animal law.

PM Shehbaz Sharif announces 14-point austerity plan

- 5 گھنٹے قبل

Pakistan Navy launches Operation Muhafiz-ul-Bahr to ensure maritime security

- 8 گھنٹے قبل

Valve’s Steam Machine may not launch this year

- ایک دن قبل

PM announces reward of Rs1.5m for each player of national hockey team

- 11 گھنٹے قبل

How to figure out your finances after a breakup

- 12 گھنٹے قبل

Special meeting on austerity policy: Federal Cabinet decides to forgo two months’ salaries

- 11 گھنٹے قبل

Downdetector and Speedtest sold to Accenture for $1.2 billion

- 14 گھنٹے قبل

Pakistan targeting militant hideouts in Afghanistan: Tarar

- 11 گھنٹے قبل

Berger in lead as rain takes teeth out of Bay Hill

- 11 گھنٹے قبل

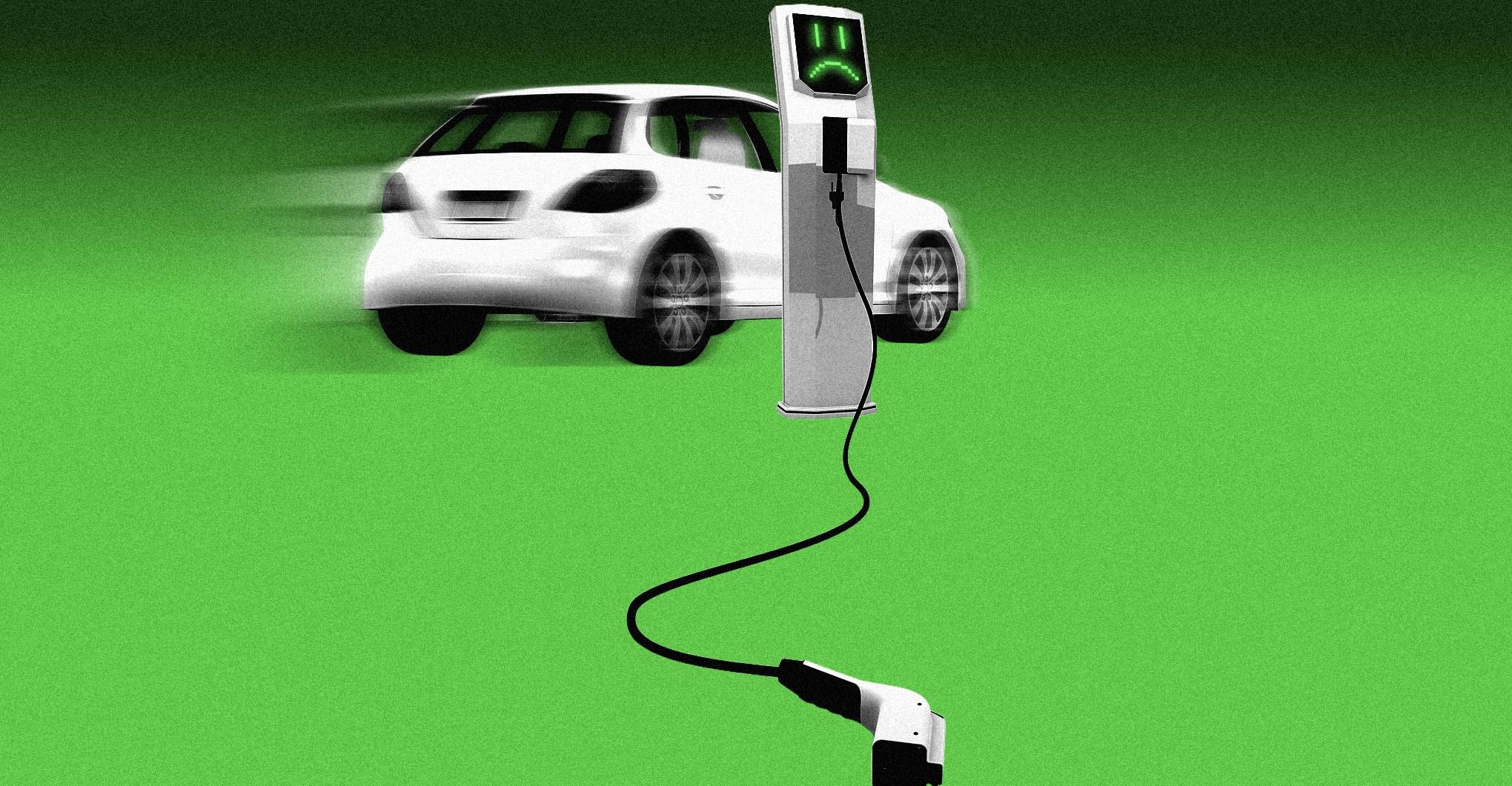

The uncomfortable truth about hybrid vehicles

- 14 گھنٹے قبل

World leaders are almost never killed in war. Why did it happen to Iran’s supreme leader?

- 21 گھنٹے قبل

Lee navigates wild round to lead LPGA in China

- 11 گھنٹے قبل