Regional

The worst internet outage still hasn’t happened yet

The world is still dealing with the fallout from the CrowdStrike screwup that took millions of computers offline last week. Some IT workers have had to fix each computer manually, walking from machine to machine with a USB stick, and some remote workers say t…

The world is still dealing with the fallout from the CrowdStrike screwup that took millions of computers offline last week. Some IT workers have had to fix each computer manually, walking from machine to machine with a USB stick, and some remote workers say they’re locked out of their computers with no fix in sight. All because of a few lines of bad code. It started in the early morning hours of Friday, July 19, when the cybersecurity company CrowdStrike pushed an update to its millions of customers. Unfortunately for all of them, there was a mistake in the code that caused Windows computers to crash repeatedly. This caused lots of problems for airlines, banks, hospitals, TV broadcasters, government agencies, and everyone who interacted with these organizations as the dreaded “blue screen of death” took over millions of computers. It took CrowdStrike just 78 minutes to identify the problem and issue a fix, but because many computers needed to be manually restarted, the problems persisted through the weekend and into this week. As of Wednesday morning, Delta Air Lines was still experiencing delays due to the outage. The ongoing Delta flight cancellations separated countless unaccompanied minors from their parents for days. This is all annoying and anxiety-inducing. But a massive outage like this — whether caused by a faulty update, as was the case with CrowdStrike, or by a cyberattack — could have been much worse. Much worse. Like, getting kicked back to the 19th century overnight worse, and it’s not clear what we can do to stop it. “This was just an accident,” Mark Atwood, an open source policy wonk and former Amazon employee, told me. “This could have been something that … just turned everybody’s computers into bricks, possibly unrepairable.” The really scary thing is that there’s honestly not much you or I can do to prevent a catastrophe like that from happening in the future. If you work for CrowdStrike, sure, you could do your part, but for the most part, building a more resilient internet is a job for the federal government. As trite as it may sound, one thing you can do is call your representatives in Congress and demand action. Because even if there’s not much you can do on an individual level to prevent the next big internet outage or cyberattack, you will likely be affected. One big problem — and a key reason why this outage was so huge — is that CrowdStrike controls so much market share, and its software is so deeply integrated into so many computers, that one bad update can bring them all down. Regulations require companies in critical industries, like health care and banking, to protect people from harm, which means they must follow cybersecurity guidelines and use endpoint security software, which protects internet-connected devices from cyberattacks. CrowdStrike tends to be the default option to comply with these regulations, and in 2021, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) even picked CrowdStrike to secure multiple government agencies. CrowdStrike now controls nearly 25 percent of the market for endpoint security. So when CrowdStrike pushes out a bad update, a lot of people are affected. This particular incident affected 8.5 million Windows devices, according to Microsoft. Lawmakers and regulators can and should learn from this CrowdStrike fiasco. It could be an opportunity for the federal government to redouble its efforts at improving cybersecurity and for security companies to do better. We have to demand they build products that are truly secure, says Dan O’Dowd, CEO of Green Hills Software and founder of the Dawn Project, an organization dedicated to making computers safe for humans. “We know how to do it. It’s been done for years and years in the military and in aviation,” O’Dowd told me. “But it does cost more, and people just have to accept that we’re going to have a somewhat higher cost, so that we don’t lose it all.” Cybersecurity experts talk about “the big one” a lot these days, and that’s what O’Dowd is referring to when he says we could lose it all. [Image: The global outage brought down information screens on the New York City subway on July 19. https://platform.vox.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/07/GettyImages-2162028098.jpg?quality=90&strip=all] The big one might involve hackers attacking physical infrastructure, like the power grid, water treatment plants, or shipping ports. Bad actors could target elections, hack voting machines, and spread misinformation. These kinds of things are actually already happening, but so far, there has not been a truly catastrophic outage or an attack so successful that it’s brought down large swaths of modern society. Not yet, at least. The CrowdStrike incident should be a wakeup call, a reminder that the big one is coming and that there’s more we could do to stop it. Republican lawmakers have called on CrowdStrike CEO George Kurtz to testify before the House Homeland Security Committee to explain what happened to cause the outage and what the company was doing about it. CrowdStrike told me it was “actively in contact with relevant congressional committees,” and on Wednesday published a preliminary incident report detailing what went wrong and how it planned to prevent something like this from happening in the future. Attention on Capitol Hill may also signal interest in legislation to create new regulations for the cybersecurity industry, although nothing has been announced. Meanwhile, FTC Chair Lina Khan is drawing attention to how the concentration of power can mean “a single glitch results in a system-wide outage, affecting industries from healthcare and airlines to banks and auto-dealers.” She seems to suggest that a better regulated cybersecurity industry could reduce that harm. Others, including Atwood, have pointed out that, in some ways, the regulations are in place, but companies like CrowdStrike still aren’t following best practices. “Everyone believed there was no silver bullet, there was no cure for this other than try to think harder,” Atwood told me. “There are still bullets and best practices that, if you do them, the odds of making mistakes like this fall a lot.” Truth be told, there’s no easy way to make our networks and computers completely secure. But the federal government is continuing to try. It established CISA in 2018 to do everything from securing elections to protecting the power grid from electromagnetic pulse, or EMP, attacks. President Joe Biden also issued an executive order in 2021 to improve the nation’s cybersecurity with 55 new requirements, almost all of which have now been completed. (That executive order is also what led CISA to pick CrowdStrike as the federal government’s endpoint security partner.) And this year, following a series of breaches during the 2020 midterm elections, CISA also launched a program to bolster election security, including protections for non-voting systems, like voter registration databases. That just represents a handful of the federal government’s efforts to avoid a catastrophic cyberattack or outage. And the cybersecurity industry is growing in lockstep with increasing anxiety about such a disaster. Spending on cybersecurity rose about 70 percent from 2019 to 2023, according to Moody’s, and the rise of generative AI will only complicate the picture in the years to come. The 2024 election cycle has already seen AI-generated robocalls that mimicked President Biden’s voice and told people not to vote, which does not sound as frightening as a cyberattack bringing down a power plant, but is an attack on democracy nevertheless. The big one is still out there, lurking in some unknown future, waiting for the right string of events to occur and lead to catastrophe. Some of the worst nightmare scenarios have actually already happened, only not at a global scale. Ransomware attacks on hospitals and health care providers that threaten lives are a regular occurrence in the US these days. After taking out a portion of Ukraine’s power grid with a cyberattack in 2015 and 2016, Russia used a novel cyberattack to cut the heat to 600 buildings in the Ukrainian city of Lviv this past January. So far, and very luckily, we have not seen a cyberattack lead to a nuclear disaster, but such a thing is not out of the realm of possibility. “So I just rewatched Chernobyl last week,” Atwood said, referring to the HBO series about the 1986 nuclear disaster. “And that was one of the key lines: Why worry about something that hasn’t happened yet?” That’s how some cybersecurity executives think about the unimaginable, he told me, even when their own employees are warning against it. If we’ve learned anything from the past week — or even the past decade — it’s that the scale of outages and cyberattacks is getting larger as the world depends more on internet-connected devices to run itself. There’s no better time than now to reconsider whether we’re doing enough to stop the next one. A version of this story was also published in the Vox Technology newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one!

Continue Reading

-

Entertainment 2 days ago

Entertainment 2 days agoBTS Jin's heartfelt shoutout to ARMY leaves fans in tears

-

Business 1 day ago

Business 1 day agoECNEC approves development projects worth Rs172.7bn

-

Pakistan 1 day ago

Pakistan 1 day agoNon-recovery of abducted boy leads to strike across Balochistan

-

Sports 2 days ago

Sports 2 days agoPakistan win toss, opt to field first against Zimbabwe in 1st ODI

-

Pakistan 12 hours ago

Pakistan 12 hours agoArmy called in Islamabad, ordered to shoot miscreants on site

-

World 1 day ago

World 1 day agoDonald Trump completes 15-member cabinet

-

Regional 1 day ago

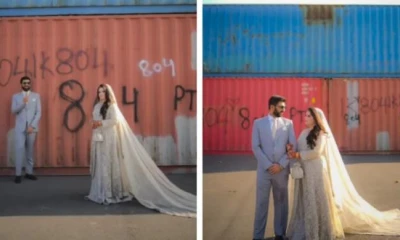

Regional 1 day agoCouple's wedding photoshoot in front of containers in Islamabad goes viral

-

Sports 8 hours ago

Sports 8 hours ago2nd ODI: Zimbabwe set Pakistan target of 146 runs to win