Regional

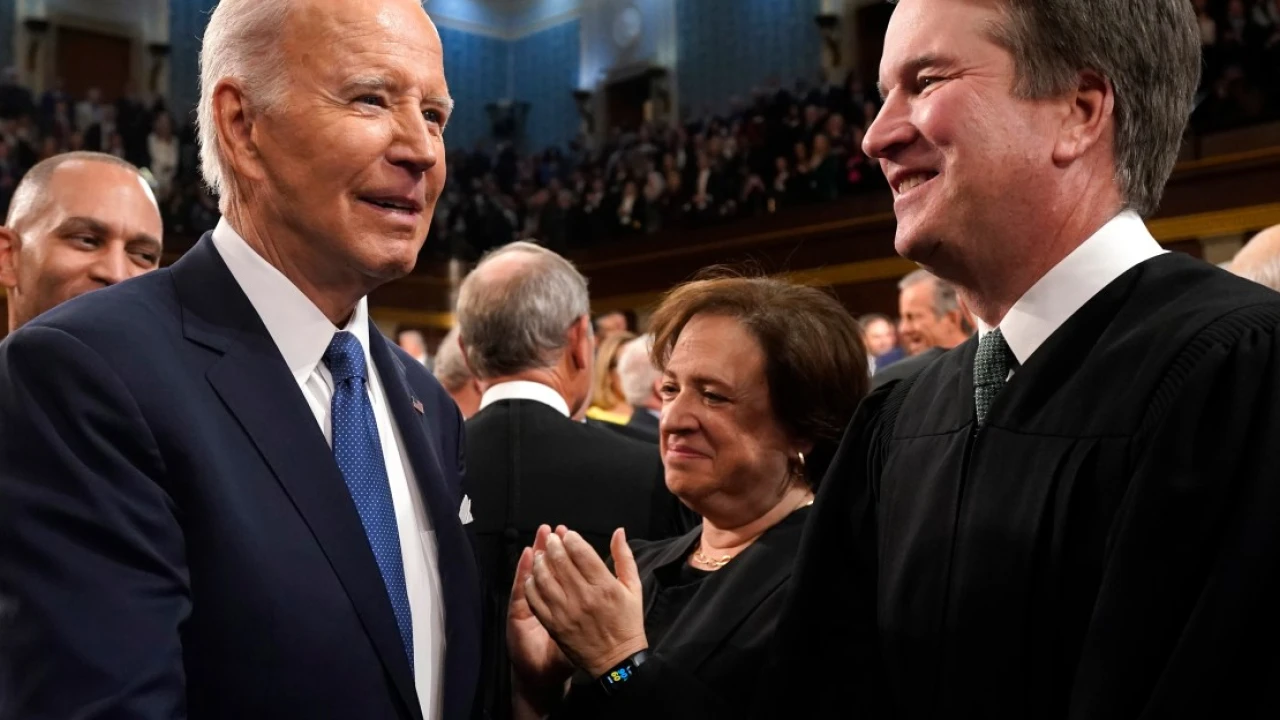

Biden’s new Supreme Court reform proposals are mostly useless

On Monday, President Joe Biden announced three proposals to reform the Supreme Court: term limits for justices, a binding code of Supreme Court ethics, and a constitutional amendment overturning the Court’s decision allowing sitting presidents to violate the …

On Monday, President Joe Biden announced three proposals to reform the Supreme Court: term limits for justices, a binding code of Supreme Court ethics, and a constitutional amendment overturning the Court’s decision allowing sitting presidents to violate the criminal law. Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic Party’s presumptive presidential nominee, also endorsed the proposals. But if you’re hoping these ideas will rein in a Court that’s essentially become the policymaking arm of the Republican Party, expect to be disappointed. Amending the Constitution is virtually impossible — it requires approval from three-quarters of the states — so Biden’s proposal to amend the Constitution to overturn the presidential immunity decision in Trump v. United States (2024) is almost certainly dead on arrival. Similarly, the term limits proposal is at odds with Article III of the Constitution, which provides that justices “shall hold their offices during good behaviour,” language that’s historically been understood to protect judges unless they engage in serious misconduct. So that proposal is equally dead. Proposing a constitutional amendment is not entirely useless. By proposing two amendments targeting the Supreme Court, Biden makes clear that his Democratic Party opposes much of the Court’s recent behavior, much like President George W. Bush used a proposed constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage in 2004 to communicate to voters that Republicans were the anti-gay party. But Bush’s amendment was never enacted, and Biden’s amendments almost certainly won’t become law, either. The call for a binding ethics code, by contrast, could potentially impose some limited constraints on the Court. The Constitution states that most of the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction must be exercised “under such regulations as the Congress shall make.” So Congress should have the power to enact a Supreme Court ethics code with an ordinary statute, rather than with a constitutional amendment. It’s unclear, though, whether the justices would follow such a code if Congress enacted one. At least one justice, Samuel Alito, has claimed that such an ethics code would be unconstitutional. If Congress were to pass such a code, and the justices wanted to ignore it, all they’d need to do is sign onto whatever argument Alito came up with to justify striking down the code. Even if the same justices who concluded that presidents are above the law decided not to declare themselves immune from ethical reform, a binding ethics code would do little to cure the Court’s partisanship. While two of the justices, Alito and Justice Clarence Thomas, accepted lavish gifts from Republican billionaires, seven of the nine justices have thus far not been caught in similar scandals. Four of the Court’s six Republicans might not be affected in any serious way by an ethics reform law. While a binding ethics code might stop Thomas from sailing around the world on billionaire Harlan Crow’s yacht, it wouldn’t stop him from voting to, say, eliminate freedom of the press. Biden’s proposals, in other words, are mostly symbolic. The ethics proposal is meaningful but limited in scope. And the two other proposals? They won’t accomplish anything that couldn’t also be accomplished by a presidential press conference denouncing the Supreme Court. A constitutional amendment will not pass The Constitution, according to University of Texas law professor Sanford Levinson, “is the most difficult to amend or update of any constitution currently existing in the world today.” Three-quarters of the states must ratify any constitutional amendment, a requirement that virtually ensures that either major political party can block any amendment, even if the other party wins supermajorities in Congress. This explains why the Constitution has only been amended 27 times in all of American history, and 10 of those amendments was the Bill of Rights, which was enacted almost immediately after the Constitution took effect. The last time the Constitution was amended was more than 30 years ago, in 1992. And that was a very minor amendment involving congressional pay. As President Franklin Roosevelt once said, “No amendment which any powerful economic interests or the leaders of any powerful political party have had reason to oppose has ever been ratified within anything like a reasonable time.” Indeed, as a practical matter, any amendment is likely to fail if it garners opposition from any substantial interest group. American history is replete with popular proposed amendments that failed because of strong but narrow opposition from such a group. In 1924, supermajorities in Congress proposed a constitutional amendment to overrule the Supreme Court’s decision in Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), which struck down a federal ban on child labor. The amendment died largely due to opposition from cotton mill owners, but oddly enough also because of opposition from the Catholic Church, which feared that a child labor amendment would lead to federal regulation of parochial schools. Similarly, the Equal Rights Amendment, which would have written gender equality into the Constitution, seemed destined to become law after Congress proposed it in 1972. In one year alone, 22 states ratified it. But then anti-feminist activists like Phyllis Schlafly organized against it, spreading fears that the amendment would mandate unisex bathrooms and even lead to (gasp!) same-sex marriages. In the end, the required 38 states did ratify the Equal Rights Amendment, but not before a 1982 deadline set by Congress. There is, however, a lesson to be garnered from these two failed amendments. A federal child labor ban is now law, not because proponents of the child labor amendment eventually overcame opposition from the cotton mills but because the Supreme Court overruled Hammer in 1941 after Roosevelt appointed several new justices to the Court. The ERA is not part of the Constitution, but a series of Supreme Court decisions — many of which were argued by future Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg — established that “a party seeking to uphold government action based on sex must establish an ‘exceedingly persuasive justification’ for the classification.” Thus implementing a prohibition on sex discrimination by the government that is almost as strong as the prohibition proposed by the ERA. If Democrats want to overturn the Supreme Court’s error in the Trump decision, in other words, their best bet is to follow the same playbook Republicans followed to overturn decisions like Roe v. Wade. Because it is virtually impossible to amend the Constitution by writing a new amendment into the document, constitutional disputes in the United States are resolved by the judicial appointments process. Whoever controls the Supreme Court controls the Constitution. Imposing term limits on the Supreme Court would also require a constitutional amendment President Biden’s term limits proposal calls for “a system in which the President would appoint a Justice every two years to spend eighteen years in active service on the Supreme Court.” This is a longstanding proposal that has, at times, enjoyed bipartisan support. Former Texas Republican Gov. Rick Perry, for example, offered a similar proposal in a 2010 book. It’s hard to imagine such an idea garnering Republican support today. Republicans, after all, enjoy a supermajority on the current Supreme Court. Term limits endanger GOP control of the judiciary. The Constitution is widely understood to allow justices to serve for life. That said, there are some academic arguments that the Constitution’s language allowing justices to keep their “office” during “good behaviour” isn’t entirely airtight. I’ve argued, for example, that future appointees to the Supreme Court could potentially be term-limited without a constitutional amendment because they could be appointed to a different “office” — one that only allows them to sit on the nation’s highest Court for 18 years before they are rotated onto a lower court. But even if this argument is correct, it won’t do anything about the Court’s current 6-3 Republican supermajority. Other scholars have made other arguments that could support imposing term limits with an ordinary act of Congress. Yale law professor Jack Balkin, for example, suggested that justices who have served more than 18 years could be stripped of most, but not all, of their authority to hear cases. But let’s be realistic. If Congress does enact an ordinary law imposing term limits on the justices, the constitutionality of that law would ultimately be resolved by the Supreme Court. And unlike, say, Donald Trump’s arguments that he was allowed to commit crimes while he was president, the argument that justices serve for life actually has a strong basis in the Constitution’s text. So the likelihood that the justices would allow themselves to be term-limited, at least without a constitutional amendment, is vanishingly small. The justices obviously have an interest in keeping their jobs. And the text of the Constitution is actually on their side. It’s not clear that the Supreme Court would allow an ethics reform law to take effect Ethics reform would do nothing to make the Supreme Court less partisan or less ideological, but it could prevent Justice Thomas from taking millions of dollars in gifts from Republican billionaires. It could also stop Justice Alito from going on another $100,000 trip paid for by a different GOP billionaire. These are worthy goals. Thomas’s and Alito’s corruption would not be tolerated in any other part of the federal government. Members of Congress and their staff, for example, are typically forbidden from accepting gifts worth more than $50. There are, however, good reasons to doubt whether the justices would comply with a law prohibiting corrupt behavior. In a 2023 interview published in the Wall Street Journal, for example, Alito claimed that “no provision in the Constitution gives [Congress] the authority to regulate the Supreme Court — period.” Alito is incorrect. Article III of the Constitution provides that the Court must exercise its authority to hear appeals from lower courts “under such regulations as the Congress shall make.” But the text of the Constitution also means little if a majority of the justices are willing to ignore it. Thus far, moreover, the Court has allowed Alito to get away with defying Congress. Last May, after Alito was caught flying two flags associated with the MAGA movement and efforts to overturn President Biden’s victory in the 2020 election (Alito has blamed the flags on his wife), several members of Congress asked Alito to recuse from cases involving Trump’s failed attempt to steal the election and the January 6 insurrection. Alito’s recusal was arguably required by a federal statute, which provides that “any justice, judge, or magistrate judge of the United States shall disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” But in his letter refusing to recuse, Alito rather pointedly ignored this statute, instead pointing to the Court’s non-binding internal ethics code, which states that “a justice is presumed impartial and has an obligation to sit unless disqualified,” to justify remaining on two cases. Alito, in other words, seems to believe that only the Court gets to decide which ethical rules the justices must follow. And no justice stepped in when Alito thumbed his nose at the recusal statute enacted by Congress. Which isn’t to say that Alito’s misbehavior is a reason for Congress to stay its hand. No government official should be allowed to accept lavish gifts from politically interested billionaires. And a federal statute could potentially open corrupt justices like Thomas or Alito to real consequences or even prosecution, even if that prosecution were eventually struck down by Thomas and Alito’s fellow justices. But the fact remains that ethics reform would be limited in scope. It would not stop the justices from implementing Republican Party policies from the bench. And it would likely lead to a protracted battle with justices who believe that ethical constraints are for people less important than them. So how can the Supreme Court be reformed? One pathology of the Constitution is that it does not permit moderate judicial reforms such as term limits, but it absolutely permits highly disruptive solutions such as adding more seats to the Supreme Court and immediately filling them with Democrats. The Constitution permits Congress to decide how many justices there will be, and that number has varied from as few as five to as many as ten. But court-packing is a dangerous proposal that threatens to delegitimize the entire federal judiciary, including decisions that are far less reckless than the Court’s decision in Trump. And it could trigger massive resistance in red states that may not voluntarily comply with a decision that, say, reinstates abortion rights — at least if that decision comes from a packed Court. It could also set off a cycle of retribution where each party adds seats to the Supreme Court whenever it controls Congress and the presidency until the Court has dozens of justices, all of whom are political hacks. I’ve argued that court-packing is justified if the justices become an existential threat to US democracy but it is a weapon that Congress should deploy only as a last resort. Congress does have other ways to rein in a rogue judiciary. While the Constitution forbids Congress from reducing the justices’ salaries, it could strip the Court of its staff and evict the justices from their government-provided office space. The Constitution also permits Congress to make “exceptions” to the Court’s jurisdiction, a provision that arguably allows it to strip away the justices’ power to hear certain matters. Still, a jurisdiction-stripping law could run into the same problems that could face a congressionally imposed ethics code. If the justices don’t want to be bound by it, they could simply strike it down. Realistically, in other words, the most promising way to eradicate decisions like Trump and to fill the Court with justices who will not mimic Thomas or Alito’s corruption is the same way that Republicans eliminated decisions like Roe that they disapprove of. Democrats need to win elections while simultaneously organizing against Supreme Court decisions they don’t like. Trump was a 6-3 decision. It is two Supreme Court appointments away from becoming a bad memory of a more authoritarian era. Men like Thomas and Alito, in other words, are likely to be defeated at the polls or not at all. If voters do not want to be ruled by these men, they can frustrate them by voting to elect Kamala Harris and a Democratic Congress in November. And then they can keep doing so until Republicans are in the minority on the Supreme Court.

Continue Reading

-

Pakistan 2 days ago

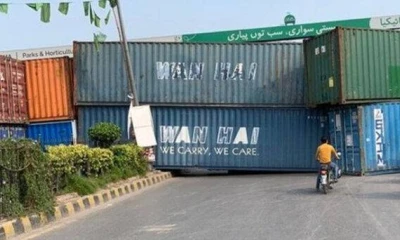

Pakistan 2 days agoGovt to suspend internet services amid PTI protest

-

Pakistan 2 days ago

Pakistan 2 days agoFiring on KP govt’s chopper in Parachinar

-

Pakistan 1 day ago

Pakistan 1 day agoPTI founder can only get relief from courts, says Ahsan Iqbal

-

Regional 9 hours ago

Regional 9 hours agoSecretary Schools Punjab announces winter vacation dates

-

Regional 2 days ago

Regional 2 days agoCM Maryam visits Nishtar Hospital, suspends paramedics over AIDS spread

-

Pakistan 2 days ago

Pakistan 2 days agoNACTA warns terrorists may target PTI protest in Islamabad

-

Pakistan 2 days ago

Pakistan 2 days agoNo protest or rally is allowed in Islamabad, says Naqvi

-

Sports 1 day ago

Sports 1 day agoPakistan win toss, opt to field first against Zimbabwe in 1st ODI