Why have our winters gotten so weird?

How climate change is messing with our winters.

Bitter cold continues to grip the United States as unusual freezing temperatures stretch as far south as Florida this week. Even more chilly weather is in store through the weekend, putting more than 80 percent of the US population under some type of cold weather advisory.

But this jarring cold snap is sandwiched between the end of what was the hottest year on record and the start of another year that could be even hotter. And even as temperatures plunge to new depths, the recent weather isn’t remotely enough to derail an ominous trend.

As the climate changes, the bottom of the temperature scale is rising faster than the top. This pronounced winter warming is often less palpable than the triple-digit summer heat waves that have become all the more frequent across much of the country, but no less profound.

According to Climate Central, more than 200 locations around the United States have lost almost two weeks of below-freezing nights since 1970. By 2050, 23 states are projected to lose upward of a month of freezing days.

“In general, winters have been getting warmer across the country, and really across the world,” said Pamela Knox, an agricultural climatologist at the University of Georgia extension. “It turns out that the colder seasons are warming up more quickly than the warmer seasons.” Warmer winters are one of the strongest examples of how humanity has changed the world with its ravenous appetite for fossil fuels, which emit greenhouse gases into the atmosphere and drive up global temperatures.

That doesn’t just mean fewer good ski days or the end of white Christmases for some regions; cold weather is an important, essential signal for plants and animals, and losing it has far-reaching effects on the economy, food production, and health.

Why winters in particular are heating up

Though Earth is warming on average, those changes aren’t distributed evenly across the planet or throughout the year. The Arctic, for example, is warming about four times as fast as the rest of the world as the sunlight-reflecting ice yields to the darker, heat-absorbing ocean below.

The cold seasons are also heating up disproportionately further south, albeit at a slower pace than the North Pole. According to the fifth National Climate Assessment, a report by 14 US government agencies published last year, “Winter is warming nearly twice as fast as summer in many northern states.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25234579/figure2_7.jpeg)

Why? Winters, it turns out, tend to have a stronger response to heat-trapping gases than summers. That’s not just due to carbon dioxide and methane, but also water vapor. For every 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit increase in temperature, air can hold on to 7 percent more moisture. “Cold atmospheres are especially sensitive to the additional moisture because the air is usually dry to start with, and a little more water vapor means a lot more heat is trapped near the surface,” Jennifer Francis, a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, an independent team of climate scientists, wrote in an email.

In places where winter temperatures are rising above the freezing point, that’s leading to more rain than snow. But in areas where winter is warming but not yet above 32 degrees Fahrenheit, that extra moisture in the air can lead to more snowfall.

“Snowfall is generally declining except where it’s still plenty cold enough for snow (rather than rain) to fall,” Francis said. “There is also a clear increased frequency of heavy precipitation events in all seasons.”

Warming winters could also have some paradoxical effects and may even contribute to sudden cold snaps like the one underway across the US, although scientists are debating the mechanisms at work. One idea is that the rapid warming in the Arctic is destabilizing the polar vortex, the band of fast-moving air that typically contains frigid air to the far north. The National Climate Assessment notes that “some recent studies suggest that Arctic warming results in increasing disruptions of the stratospheric polar vortex that cause cold air from the Arctic to spill down over the United States, as seen in recent severe winter weather events such as the February 2021 cold snap that affected large parts of the country.”

However, with more greenhouse gases accumulating in the atmosphere, more heating is in store for the coldest regions of the world, which in turn will raise sea levels, alter ocean currents, and warp weather patterns around the globe. This is already having far-reaching effects near the equator, from reshaping shorelines to hampering harvests of prized fruit.

You’ll miss this cold when it’s gone

Consider the peach. For the state of Georgia, it’s kind of its thing.

Georgia’s official nickname is “The Peach State.” “George peach” is a trademarked paint color. They’re on the license plate. The Atlanta metro area has more than 70 Peachtree streets.

These perfect, pinkish, plump, pulpy, pitted produce are products of pride for the state (despite Georgia ranking a distant third in peach production). So, the loss of 90 percent of the crop last year — the worst harvest since at least 1955 — hit Georgians hard. Even as prices tripled, many farmers didn’t have any peaches to sell, leaving picky connoisseurs to scramble for what was left.

“Buying peaches from any other state is completely out of the question,” Henryk Kumar, director of operations at the Butter & Cream ice cream shops in Georgia, told CNN last year.

Like much of the country, Georgia was hammered by severe and often hot weather in 2023. The extremes proved to be an especially deadly combination for the state’s precious fruit. A heat wave in February followed by two back-to-back cold snaps then heat waves again in the summer devastated the crop.

The string of weather last year was especially unlucky, but warmer temperatures from November through February are posing a long-term threat to the future of Georgia peaches.

Georgia isn’t known for chilly winters, but what little cool weather it gets is precious. To produce ample fruit, peach trees require a minimum number of chill hours at temperatures below 45 degrees Fahrenheit. Depending on the variety, that requirement can range from 500 to 800 hours. The cool weather signals the tree to save up energy and resources. Once a tree reaches its minimum cold exposure, it can suspend its dormancy and resume growing in the spring.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25234718/GettyImages_1568145839.jpeg)

However, with warmer winters, peach trees are experiencing seasonal insomnia. It’s disrupting the timing of when they blossom, making it harder for farmers to ensure they’re pollinated and end up bearing fruit. “A lot of times they bring in bees, so they want to have the maximum amount of pollination in a certain amount of time,” Knox said. “What happens when you don’t get enough chill hours is that the plants will still produce buds, but they’re not all ready to bloom at the same time.”

If warming continues at its current pace, Georgia will face more frequent seasons where it won’t be cold enough to grow many common peach varieties. The optimal growing regions for fruit like peaches and apples are going to shift northward, according to Knox: “Maybe they’ll grow more in north Georgia rather than in central Georgia where they do now.”

This is just one example of how much the world as we know it counts on cool weather and the stakes of losing it. Another critical winter threshold is the freezing point of water. In places like the Sierra Nevada, snow serves as a water battery, charging up in the winter to power streams and rivers in the western US throughout the year. Warmer winters can thus fuel a weather whiplash with flooding in the winter and drought in the summer, even if overall precipitation doesn’t change very much.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25234565/freeze_thaw_download1_2023.png)

The loss of cold weather in the winter can also amplify warming through the spring and summer. “Earlier loss of spring snow cover more generally means that the strong spring sun can dry out the soil earlier, and when the soil dries out, it can warm up much faster,” Francis said. “This is contributing to summer heat waves, droughts, and more intense fire seasons.”

Warmer winters do have some upsides. Since the beginning of the 20th century, warming has extended the growing season by two weeks. For farmers growing annual crops like corn or wheat, that can let them squeeze in more plantings in a year. Last year, the US saw increases in soy and wheat production, as well as a record corn harvest. But for orchards that bear fruit once a year, that longer season doesn’t offer much help.

Rising winter temperatures also mean that severe chills and sudden frost events may be less likely in some areas. A dip below freezing after plants begin to awaken from their winter slumber can damage fragile leaves, stems, and roots, thereby hurting crop yields. But even in a warmer climate, frost events can still occur within the ordinary chaos of weather — as it did with Georgia’s peaches last year — though their timing may change. “The national climate system is like a bowl of jello,” Knox said. “It’s always jiggling.”

13 khwarij killed in different IOBs in KP: ISPR

- 13 hours ago

PM Shehbaz unveil statues of Quaid-e-Azam, Mao Zedong in Islamabad

- 13 hours ago

Two more polio cases in Pakistan, toll reaches 67 this year

- 2 minutes ago

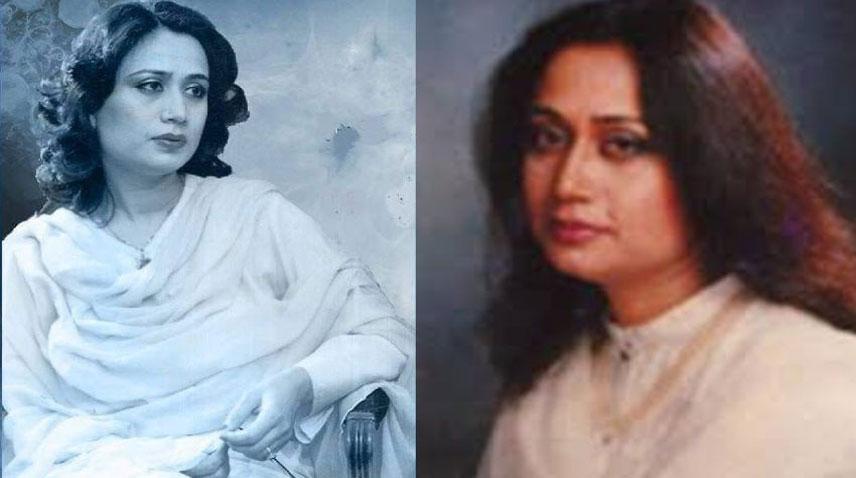

30th death anniversary of poetess Parveen Shakir observed

- 13 hours ago

Babar Azam reaches important milestone in Test cricket

- an hour ago

17th death anniversary of Benazir Bhutto today

- 42 minutes ago