The creators are “little more than boys” and clean and neat, like salespeople or bankers. They are looking for manuscripts for their Library. No fiction — none of that inauthentic literature. They want diaries, people’s deepest, innermost thoughts: “true, authentic documents reflecting the real spirit of the people.” The promise is that the Library will connect lonely souls, bringing them together, letting them make friends. For a fee, a reader can be put in touch with the writer of the documents. “How fast, almost explosive, its growth was!”

- Home

- Technology

- News

This 1977 horror novel is about social media

The Twenty Days of Turin is oddly prescient about what happens when people are atomized and surveilling each other.

It is after the Library opens that the grisly murders begin.

A lure for the morbidly isolated

I read The Twenty Days of Turin more than a month ago, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it. It is a political allegory — Giorgio de Maria was writing during Italy’s Years of Lead, marked by near-constant terrorist violence. Though there was violence on both the right and left, the notable emergence of neofascist groups resulted in the biggest body count: a 1985 bombing in Bologna that killed 85 and injured more than 200. Worse, the neofascists appeared to have a relationship with law enforcement and the government itself.

The book was translated into English in 2017 by Ramon Glazov. I have no idea how I ended up with The Twenty Days of Turin or who recommended it. It simply happened to me, just as the narrator of the book begins receiving letters from an unknown correspondent. Of course, the unnamed narrator writes back, which perhaps seals his fate.

Perhaps the first clue that the Library is not as wholesome as its inventors suggest is its location: a former church-run sanitarium. And sure enough, it becomes a lure for the morbidly isolated.

Some of these manuscripts document perverse desires — a grandfather, in his seventies, writes at length of his lust to deflower an 18-year-old, the same age as his grandchildren; a constipated woman in her 40s wants a young man to help her defecate — and some are simple tirades against the publishing industry itself. Still, the overwhelming impression is unholy:

There were manuscripts whose first hundred pages didn’t reveal any oddity, which then crumbled little by little into the depths of bottomless madness; or works that seemed normal at the beginning and end, but were pitted with fearful abysses further inward. Others, meanwhile, were conceived in a spirit of pure malice: pages and pages just to indicate, to a poor elderly woman without children or a husband, that her skin was the color of a lemon and her spine was warping — things she already knew well enough. The range was infinite: it had the variety and at the same time the wretchedness of things that can’t find harmony with Creation, but which still exist and need someone to observe them.

The Twenty Days of Turin was originally published in 1977, but it’s impossible not to read about the Library and think of Silicon Valley’s boy wonders creating social media. Anyone who’s been in an online community for any length of time has witnessed the perversions, meltdowns, bullying, and otherwise bizarre human behavior de Maria imagines in his Library.

These people could rescue each other if only they could connect

The narrator of this slim horror volume is attempting to reconstruct a period of 20 days where people couldn’t sleep and instead roamed the streets. These insomniacs, many of them patrons of the Library, were murdered in ways that seem shocking, even inhuman. The Library was closed and the murders stopped — and no one seems to know exactly why. And now, 10 years later, the narrator is trying to piece together exactly what happened in that time.

As in any detective story, the narrator is warned against looking farther. As in any detective story, he ignores this warning. Even though very few citizens of Turin want to acknowledge those 20 days of terror, it is almost impossible not to notice the effects. And as the narrator continues exploring, it becomes clear that the Library may not actually be gone. He may, in fact, be in great danger.

The deaths in The Twenty Days of Turin are pointless, not unlike the mass shootings that routinely occur here in the US. The goal is mayhem, with violence and fear as the organizing principles. And like the citizens of Turin, no one seems to want to look directly at the brutality, even when it’s children dying. Though there should be witnesses to the Turin insomniacs’ deaths — the other insomniacs are out and about after all — no one can quite say what’s going on. These people could rescue each other if only they could connect, but they are too atomized.

Atomized and surveilled, just like anyone who’s online. The Library is, of course, a “web of mutual espionage.” Anyone foolish enough to post their thoughts can be known by thousands of strangers; there is no way to take the words back. There is a distinct atmosphere of paranoia; anyone could be monitoring the narrator, and indeed, some people are.

The terror in Turin is, ultimately, Lovecraftian — there’s a slow burn to the discovery of what’s actually behind the people who’ve had their skulls bashed in. The pacing in de Maria’s book is impeccable, turning up the dread until it permeates every sentence. But that’s not why the book stuck with me. It stuck with me because it felt familiar. There seems, to the reader, to be a clear solution: band together against the horror. And yet, no one in the book can do it.

New Zealand beat South Africa to reach T20 World Cup final

- 8 گھنٹے قبل

The Galaxy S26 is a photography nightmare

- 15 گھنٹے قبل

The Supreme Court appears likely to let stoners own guns

- ایک دن قبل

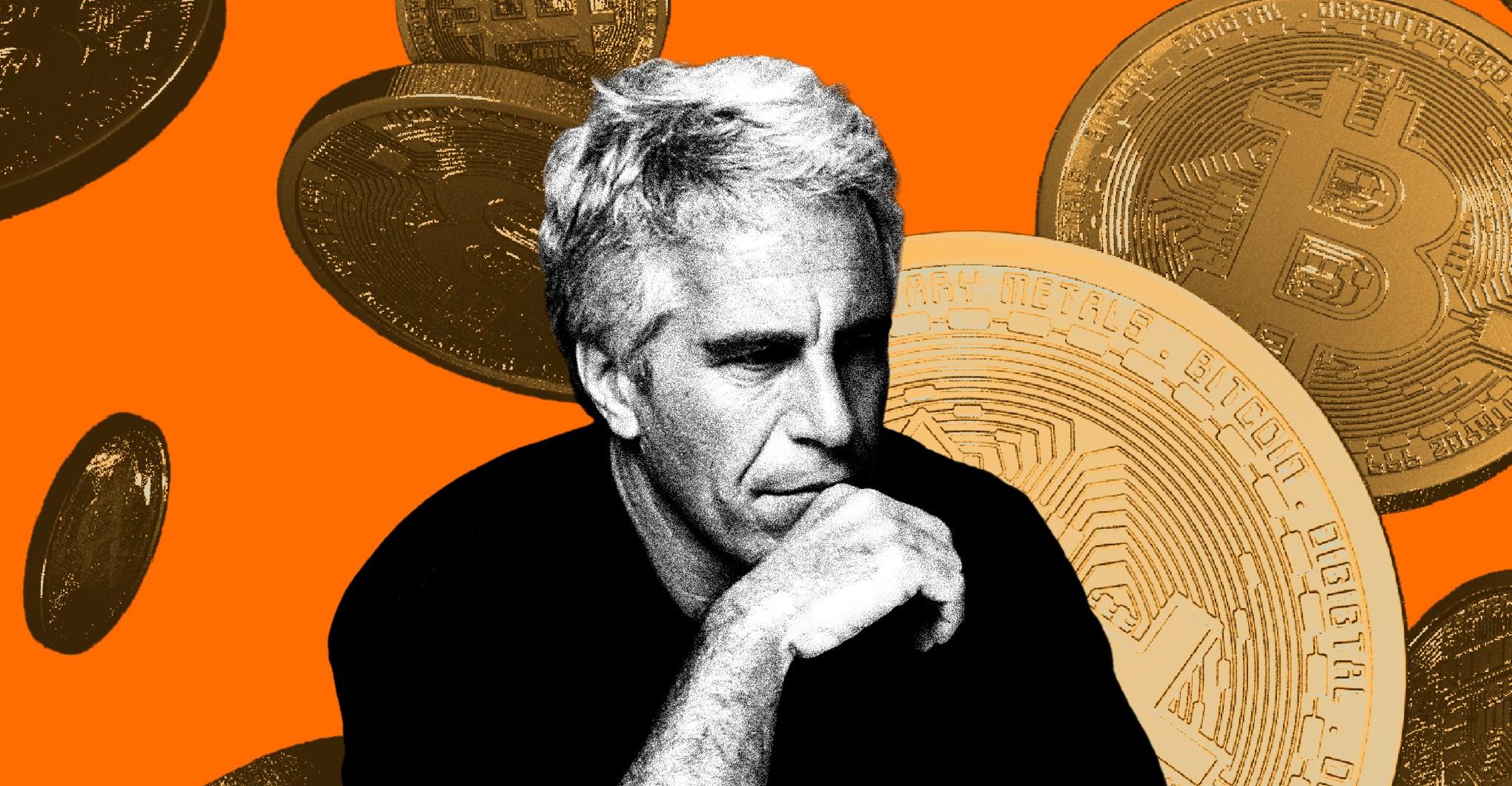

Jeffrey Epstein saw promise in Bitcoin — and its far-right supporters

- 15 گھنٹے قبل

PM takes parliamentary leaders into confidence regarding Pak-Afghan situation

- 14 گھنٹے قبل

Global oil and gas shipping costs surge as Iran vows to close Strait of Hormuz

- ایک دن قبل

Do you need to know who you’d be without antidepressants?

- ایک دن قبل

Iran Guards say launched more than 40 missiles at US, Israeli targets

- 13 گھنٹے قبل

Apple launches new generation of MacBook laptops starting at $1,099

- ایک دن قبل

Iran postpones state funeral for Khamenei: state TV

- 11 گھنٹے قبل

Iran war enters fourth day in 'smoke and blood' as markets slide

- ایک دن قبل

Use of Afghan soil against Pakistan unacceptable: CDF

- 31 منٹ قبل